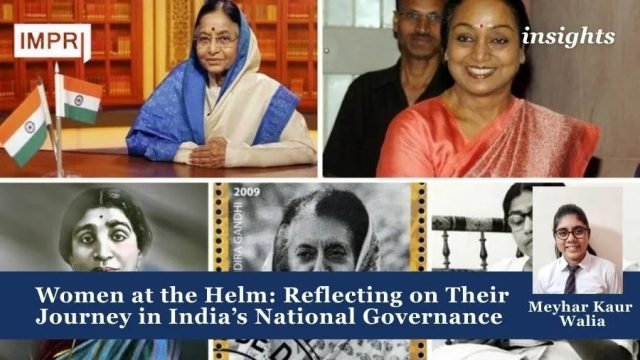

Meyhar Kaur Walia

Abstract

Theoretical frameworks that have shaped public policy and governance discourse have historically been developed through a largely patriarchal lens. These dominant paradigms often excluded or overlooked women’s lived experiences, marginalizing feminist thought and gender-based perspectives. Despite the evolving socio-political context, these historical exclusions remain deeply embedded in contemporary administrative and policy-making institutions. In the Indian context, young women, especially from marginalized castes, religions, or socio-economic backgrounds, are increasingly encouraged to engage in leadership and policy-making roles. Yet, their participation is frequently tokenistic, their voices underrepresented in real decision-making.

Background

In the pre-independence era, the women’s movement began in the nineteenth century as a social reform movement. They date back to pioneers like Savitribai Phule, who, along with her husband, Jyotirao Phule, worked to encourage women’s education and challenge caste and gender oppression. In 1848, she established Pune’s first girls’ school, defying the ‘social normal’ of the time. The movement gained momentum, and reformers like Pandita Ramabai began pressing for the rights and education of widows. At the beginning of the 20th century, women also entered the struggle for national freedom, and leaders such as Sarojini Naidu and Annie Besant highlighted women’s political rights.

The recent passage of the one-third reservation bill in Parliament marks a major advancement in institutional commitment to gender parity. However, its decades-long delay also raises critical questions about the political will behind long-overdue reforms. The most significant barrier remains the deeply rooted cultural norms that uphold and reinforce patriarchal structures. Societal attitudes that continue to support patriarchal norms often limit women’s access to leadership roles, influence voter perceptions, and affect how female leaders are treated within political parties and institutions.

From Independence Onward: Women’s Legal and Social Revolution

The influence of democracy on feminist movements in the post-independence period proved to be one of the most important formative factors on the idea of gender equality. The Constitution of India guaranteed “Equality between the sexes,” and administrative bodies were set up to create opportunities for women. Articles such as Article 14 (Equality before law), Article 15(1) (prohibition of discrimination based on sex), and Article 21 (right to life and personal liberty) served as key mechanisms in advancing women’s legal status. Many women’s organizations, such as the All India Women’s Conference (AIWC), reoriented themselves as social organizations providing services, including running schools, hostel facilities, etc.

Many scholars have categorized the women’s movement in distinct phases, namely,

- The period of Accommodation (1947-1960s), which saw the enactment of legal measures such as the Marriage Act of 1954, the Hindu Code Bill of 1955–1956. The motive of these enactments was to eradicate social issues related to marriage, divorce, inheritance, child custody, and adoption in India.

- The Period of Crisis (the late 1960s-1975), this period has been marked by economic crisis, generalized discontent, and movements against dowry deaths, leading to the Dowry Prohibition Act of 1961. During the time, politically based organizations like CPI(M) established the Shramik Mahila Sangathana around 1973-1974, and women associated with Maoist groups created the Progressive Organization of Women. The Committee on the Status of Women in India (CSWI) was appointed in 1974 to examine women’s rights amid the changing socio economic conditions, and “Towards Equality” was its report that highlighted the discrimination women faced in various sectors.

- Shift from the Rights Movement to the Welfare Movement (1975-2018). During this period, the movements confronted the cases of violence against women, missing girl child, etc. The organizations in this phase included Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), National Commission of Women (New Delhi), National Council of Women (Pune), Joint Women’s Program (Delhi), and Kali for Women (Delhi). The 73rd and 74th amendments, enacted in 1992, marked a milestone by mandating one-third reservation of the seats to be reserved for women. Laws such as the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act (2005) and amendments to the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) for enforcing stricter punishments for sexual assault, including the infamous Nirbhaya case in 2012, which sparked public outrage.

- #MeToo movement (2018-present). The 2005-2006 National Family Health Survey (NFHS) revealed that one-third of women aged 15-29 had experienced physical violence, and approximately one in ten had been a victim of sexual violence. To support the survivors of sexual harassment and assault, the #MeToo campaign was started in the United States of America (USA) in 2006 by Tarana Burke. Later, this campaign spread as a movement in the rest of the world and reached India in 2018.

The public/private dichotomy is central to the feminist movement, expressed in the slogan, ‘The Personal is Political’. It was popularized during the second wave of feminism in the 1960s and highlights the link between individual experiences and broader social and political structures. Feminists argue that most of the injustices, crimes, and violence occur against women within the confines of four walls.

Relegating the domestic world outside of the state’s purview can be seen as essentially supporting patriarchy. By treating family life as a “private” or “non-political” space, the state ignores the power dynamics, gender roles, and oppression that often exist within it. This traditional understanding is misleading, as what happens in the home is deeply rooted in societal structures and power relations. Thus, the trajectory of legal reforms and social movements in India encompasses not only the public framework but also the deeply rooted issues that originate within private spheres.

Affirmative Action for Women

The concept of equality can be seen through two lenses: equality of opportunity and equality of outcome. Equality of opportunity is concerned with initial conditions and the removal of obstacles that stand in the way of development, while equality of outcome is concerned with the end results.

From a gender perspective, if opportunities are truly equal, then everyone competes on a level playing field. While formal barriers may be removed, deep-rooted societal structures and cultural norms continue to limit women’s full participation. The equality of outcome raises important questions: ‘Are women reaching decision-making positions?’, ‘Are their voices being heard?’ If not, then equal opportunity has not achieved full equality.

It’s also essential to consider the concepts of negative and positive discrimination. Negative discrimination involves treating individuals unfairly due to their protected characteristics, like race, gender, age, disability, religion, etc. Positive discrimination, on the other hand, also known as affirmative action, is a strategy to protect members of a disadvantaged group who currently or have suffered discrimination. In the Indian context, women have historically faced systemic oppression.

Therefore, measures such as reservations and targeted support programs advance equality rather than going against it.

About the contributor: Meyhar Kaur Walia is an undergraduate student in Political Science at Gargi College, University of Delhi, India. She is a fellow of the YWLPPF 3.0 – Young Women Leaders in Public Policy Fellowship, Cohort 3.0.

Disclaimer: All views expressed in the article belong solely to the author and not necessarily to the organisation.

Read more at IMPRI:

Raksha Mantri Ex-Servicemen Welfare Fund (RMEWF),2023

Climate Finance Politics: India’s Strategic Push Ahead of COP30

Acknowledgement: This article was posted by Rashmi Kumari, a research intern at IMPRI.