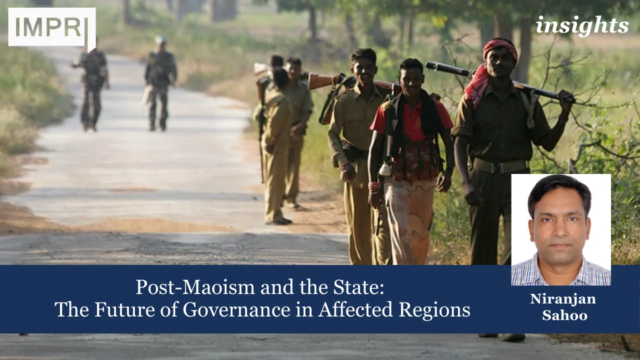

Niranjan Sahoo

India’s Fifth Schedule areas became the hotbed of Maoist insurgencies due to administrative neglect, exacerbating discontent and a lack of representation of tribal groups in local bodies. Effective governance is crucial to address these issues and mitigate the ongoing challenges in these regions.

A key element missing in the dominant discourse around the evolution and growth of the Maoist movement is governance. An overwhelming volume of empirical literature accounts the rapid growth of the Maoist movement in the 1990s and early 2000s to underdevelopment, and structural socio-economic issues. This is evident from the scores of official, non-official and scholarly articles which have attempted to study the “root causes” for insurgency in central and eastern India (popularly called the Red Corridor).

These articles have argued for an accelerated development push to address the acute material needs of an impoverished population which includes many vulnerable tribes. As a result of these articulations, the Indian state has been relying on a “two-pronged” approach (combining security and development) to counter the Maoist threat.

This does not mean other factors such as governance, justice redressal and other issues have been completely neglected in the official discourse. On several occasions, policy makers and official reports have sought to bring attention to creating good governance frameworks and quicker justice redressal mechanisms to address the long-standing grievances of the affected population. But there has been little effort to understand the governance challenges that intensified the Maoist insurgency in different cycles.

Unpacking challenges of governance

While the Maoist insurgency has evolved in different phases since the Naxalbari uprising (1967), the movement in its current avatar has largely been concentrated around the Fifth Schedule areas of central and eastern India — States with substantial tribal populations.

The Fifth Schedule was conceptualised and offered as a new social contract to the adivasis in these regions, by the framers of the Constitution, taking into account the special needs of the population. The Schedule provided a legal framework and instrumentality for governance of these tribal homelands. It offered special provisions such as the Tribal Advisory Council with three-fourth of members from the adivasi population and a special financial provision via the tribal sub-plan. Further, the Governor of each State was given discretionary powers to oversee the enforcement of these provisions, particularly with respect to checking land alienation.

However, extensive provisions notwithstanding, the local populations were subjected to the severest forms of discrimination and exploitation in everyday life. As recorded in the Planning Commission’s Expert Committee Report (2008), a vast region with abundant natural resources was reduced to penury due to state neglect and poor governance. That these special provisions were of little use is evident from tribal populations’ persistently low social and economic status compared to other social groups.

The Oxford University Multidimensional Poverty Index in 2010 ranked the region worse than Sub-Saharan Africa. Yet, for tribal populations, the far bigger challenge was how to exercise their rights over the land and forests. Despite legal safeguards and constitutional protection against arbitrary land acquisition, millions of them were dispossessed to penury. In his seminal study, writer Walter Fernades found that “more tribals have lost their land since the commencement of economic liberalisation than any time in the post-independent history”.

Thus, while the Constitution makers imagined a new lease of life for the adivasis under the Fifth Schedule, successive governments failed to bring up appropriate governance structures to transform this lofty vision into reality. The same colonial structures and administrative forms, rules of business, and justice system were retained for Scheduled Areas, which made tribal groups, with very low literacy, barely able to understand these rules and the modern justice system.

A lack of representation

What deepened the alienation was the complete absence of locals in the administrative units implementing provisions enumerated in the Fifth Schedule. B.D. Sharma, the then commissioner of the Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes Commission, succinctly put that “the personnel who are overwhelmingly outsiders carried their attitudes, bias and lived experiences while performing day to day tasks”. Importantly, apex bodies such as a separate Ministry of Tribal Welfare, and the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes created to oversee the execution of special provisions for the tribal population, as vividly observed by the Mungekar Committee (2009), did very little to stop the exploitation.

Moreover, while the Governors are constitutionally assigned to protect the interests of adivasis in Schedule areas, not a single Governor has acted since Independence in these regions. These institutions have been further handicapped by weak and ineffective service delivery institutions such as health, education, revenue, police, and the judiciary.

The lone exception was the Panchayat Extension to Schedule Areas Act (PESA), 1996. PESA was enacted to address adivasi underrepresentation and alienation in the form of “self-governance”. These democratic forums were envisioned to create space for adivasis to take their own decisions on welfare issues, land, natural resources, livelihood and preservation of culture and their way of life.

While PESA made some substantial changes by improving political representation at the lower level of governance, key provisions were routinely violated. The Expert Committee Report (2008) found flagrant violations of PESA by the appointed officials. One of the most abused provisions has been with regards to land acquisition.

To sum up, governance maladies and relatively low political priority accorded to the Fifth Schedule in many ways created a fertile ground for the Maoist leadership to mobilise the aggrieved adivasi population against the Indian state. The growing governance deficits which directly impacted development, welfare functions and mitigation of local grievances created an opportunity for the Maoists to spread their ideologies of a people’s government (Janatan Sarkar). There is a rich body of evidence that indisputably credits tribal frustrations, anger and low trust in governance institutions as the reasons that drove many adivasis to support Maoist ideology and revolutionary missions.

Many relied on the Maoist movement as some sort of instrument to get justice from state agencies such as the police, forest and revenue departments (which they often viewed as corrupt and oppressive).

For instance, the entire Dandakaranya region largely characterised by extreme underdevelopment and poor governance was easily captured by the underground Maoists in the 1990s with the promise of providing ownership to adivasis over lands, and the forest (under the broad slogan of Jal, Jungle and Zameen). Persistent governance and development deficits created a space for Maoists to run parallel governments (offering critical services such as paramedics, schools, food rations and speedy justice through kangaroo courts) in many of their strongholds.

Need for a new imagination

Going forward, India must pay close attention to governance paradoxes that continue to plague most regions under the Fifth Schedule. In recent years, there has been visible improvement in key service functions, particularly with respect to welfare schemes and critical infrastructure (roads, electricity, telecom) in Maoist affected regions. Both the Centre and affected States have found ways to improve service delivery functions via digital technology and cash transfer. However, critical service delivery institutions such as justice, health, education, policing, and revenue functions remain thin and unsatisfactory. Persistent structural bottlenecks (under-representation of locals) in the existing governance system have a significant bearing in their effectiveness.

On the other side, crucial rights-based legislations like the Forest Rights Act (FRA) and PESA need greater political push from the Centre as well affected States. The FRA which remains a key legal tool to protect the rights of adivasis and forest dwellers to access forest resources for their sustenance is batting for its survival today.

While many core provisions have been violated by state institutions, there have also been amendments and judicial interventions in recent years which have diluted its original mandate and effectiveness. In addition, the enactment and expansion of the Compensatory Afforestation Fund (CAF) Act, 2016 has grossly diluted legal safeguards, apart from affecting the livelihoods of forest dwellers in India.

Similarly, PESA despite initial promises faces growing resistance from the States concerned. Under pressure to unlock huge mineral deposits, most State governments in Fifth Schedule Areas have undermined the powers granted to Gram Sabhas under PESA, particularly on the issues of granting consent for mining/land acquisition. Incidentally, the most widespread violations of PESA has been in the most Maoist-affected State of Chhattisgarh.

Thus, going forward priorities must include the reversal of political and administrative under-representation of adivasis. While there are mandatory quotas at the local levels, considering these self-governing bodies lack real autonomy and financial power, representation remains largely performatory.

The permanent bureaucracy (overwhelmingly non-tribal) still calls the shots. Given the persistent alienation and trust deficits among the local population, the post-Maoist Fifth Schedule Areas governance vision can benefit by borrowing some feathers from the Sixth Schedule Areas which are governed by Autonomous Districts/Zonal Councils. In short, post-Maoist India needs a new governance charter.

Niranjan Sahoo is senior fellow, Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi.

The article was first published in The Hindu as The future of governance in post-Maoist India on 17th December, 2025.

Disclaimer: All views expressed in the article belong solely to the author and not necessarily to the organisation.

Read more at IMPRI:

Decoding India’s Q2 GDP: Growth Drivers and Data Integrity

The Pro-Business Pivot: How Modern Labour Codes Prioritize Industry Over Protection

Acknowledgment: This article was posted by Swati Arora, a Research Intern at IMPRI.