Saurabh Verma

Introduction

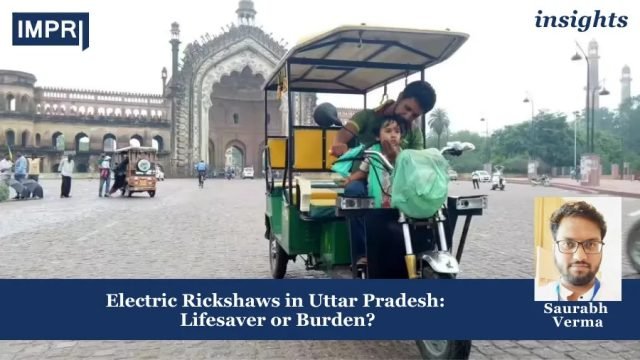

The electric rickshaw (e-rickshaw) has rapidly transformed the urban mobility landscape in Uttar Pradesh (UP). Initially introduced as a low-cost, battery-powered solution for short-distance travel, it has now become one of the most visible symbols of India’s e mobility transition. As of FY 2025, UP accounts for nearly 38% of national electric three wheeler sales, with over 266,000 registered units.

Yet, while celebrated as a climate-friendly mobility solution, the impact of e-rickshaws differs dramatically across city scales. In transitional and Tier 3 cities, they emerge as lifelines, bridging gaps in fragile mobility systems. In metropolitan centres, however, their unregulated expansion risks turning them into urban parasites—worsening congestion, crowding public transit hubs, and undermining walkability. This contrast underscores a deeper policy question: how can cities harness the strengths of e-rickshaw mobility while mitigating its unintended costs?

E-Rickshaws in Transitional and Tier 3 Cities: Informal Backbones of Mobility

Field visits across smaller towns in UP highlight the organic integration of e-rickshaws into daily life. These settlements are typically underserved by formal transit systems, with limited bus fleets and scarce metro connectivity. In this vacuum, e-rickshaws provide the de facto last-mile service—linking neighborhoods to markets, clinics, schools, and intercity bus stands.

Affordability and hyperlocal accessibility make them indispensable. A short ride often costs less than INR 20, far below auto-rickshaw fares. Informal ownership models also democratize entry into the sector, enabling drivers—often from vulnerable socio economic backgrounds to secure livelihoods. For women, elderly commuters, and schoolchildren, e-rickshaws offer safer and more direct routes compared to overcrowded buses or walking long distances. In peri-urban belts, where densities fluctuate between urban cores and agricultural peripheries, their adaptability ensures that mobility keeps pace with shifting population and economic nodes.

From an environmental standpoint, e-rickshaws deliver a climate dividend. They operate with zero tailpipe emissions, crucial in regions where air quality regularly crosses hazardous thresholds. Compared to diesel autos, their carbon footprint is significantly lower. Thus, in smaller cities, e-rickshaws not only sustain mobility but also advance social inclusion, local economic opportunity, and cleaner air.

E-Rickshaws in Metros: Congestion and Disorder

In contrast, the metropolitan experience tells a different story. Cities like Lucknow, Kanpur, Varanasi, and Ghaziabad face overwhelming growth in e-rickshaw numbers, often with little regulatory oversight. Metro stations and bus depots are congested with clusters of rickshaws competing for passengers, causing traffic bottlenecks at crucial interchange points. Without designated stands or lane discipline, they spill onto footpaths, obstruct pedestrian movement, and erode walkability. A parallel from Delhi underscores the challenge. In 2023–24 alone, Delhi Police recorded over 70,000 parking-related offences by e-rickshaw drivers, reflecting similar trends in UP’s metropolitan areas. Safety concerns compound these challenges: underage or untrained drivers, lack of formal licensing, and poor vehicle maintenance contribute to operational risks.

Thus, what functions as a flexible grassroots system in smaller towns translates into chaos and inefficiency in larger urban ecosystems. The absence of route allocation, poor enforcement, and lack of integration with formal transport systems magnify the negative externalities of e-rickshaws in metro contexts.

Policy and Planning Gaps

The divergent outcomes across city scales reveal that the vehicle itself is not the problem—policy and planning are. In Tier 3 and transitional cities, where formal bus or metro networks are sparse, e-rickshaws complement mobility needs. In metropolitan areas, however, the sheer volume and disorderly expansion of e-rickshaws expose governance gaps.

Key policy failures include:

- Lack of systematic route allocation or designated stands.

- Non-integrated planning with metro and bus systems.

- Poor charging infrastructure, leading to reliance on unsafe informal charging.

- Weak enforcement on roadworthiness, vehicle age, and safety standards.

These gaps reflect the need for context-sensitive regulation: where metros demand order and integration, smaller towns benefit from flexible informality.

Economic and Social Impacts

Beyond mobility, e-rickshaws carry significant socio-economic implications. Studies confirm that adoption enhances driver income, fosters social inclusion, and provides employment for marginalized groups (Socio-Economic Impact of E-Rickshaw Adoption, 2025). Women passengers especially benefit from safer short-distance options. Yet risks persist. Informal fare-setting leads to pricing inconsistencies. Encroachment on public spaces undermines urban design goals. Informality also leaves drivers vulnerable—lacking social security, accident coverage, or access to affordable financing for vehicle replacement. Without adequate regulation, the sector risks deepening urban disorder while also trapping workers in precarious livelihoods.

Way Forward: Toward Context-Sensitive Regulation

The case of Uttar Pradesh demonstrates that e-rickshaws can be both pillars of sustainable mobility and catalysts of congestion. The challenge lies in balancing flexibility with regulation.

For metropolitan cities, reforms must include:

- Establishing designated routes and stands near metro/bus stations.

- Integrating e-rickshaws into multimodal transport systems with digital platforms for fare regulation.

- Building charging and parking hubs to reduce street encroachment.

- Enforcing licensing, safety, and driver training standards.

For transitional and Tier 3 cities, the focus should be on:

- Supporting decentralized charging solutions.

- Expanding affordable loan schemes for drivers.

- Formalizing operations while retaining community-driven adaptability.

Most critically, state and city governments must adopt differentiated mobility governance frameworks—recognizing that what works for Lucknow may not apply to Bahraich or Shahjahanpur. A one-size-fits-all model risks undermining the unique advantages e-rickshaws offer in smaller cities.

Conclusion

The rise of e-rickshaws in Uttar Pradesh is a microcosm of India’s larger urban transition. Their role as lifelines in smaller towns and parasites in congested metros reflects not an intrinsic flaw, but the absence of tailored governance. With robust, locally adaptive policies, e-rickshaws can evolve from contested street occupants to true enablers of inclusive, sustainable, and low-carbon mobility. The future of e-mobility in India’s most populous state may well depend on how effectively it learns to manage this paradox.

References

- SPRF India (2024). E-rickshaws & Mobility in Tier II & III cities in India. https://sprf.in/powering-progress-of-last-mile-connectivity-e-rickshaws mobility-in-tier-ii-iii-cities-in-india/

- Mordor Intelligence (2025). Electric Rickshaw Market in India – Share & Size. https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/india-electric-rickshaw market

- EVreporter (2025). India EV Sales Report FY24-25. https://evreporter.com/wp content/uploads/2025/05/EVreporter-India-EV-Report-FY24-25.pdf

- WRI India (2024). Enabling the Shift to Electric Auto-Rickshaws. https://wri india.org/sites/default/files/E-auto-guidebook_WRI-India.pdf

- The Socio-Economic Impact of E-Rickshaw Adoption (2025). https://acr journal.com/article/download/pdf/1142/

About the Author

Saurabh Verma is a Lucknow-based Architect and Urban Transport Planner. He serves as a consultant to multiple government departments in Uttar Pradesh, contributing to urban governance, city planning, and urban mobility initiatives. In parallel with his consulting practice, he is engaged as an academician at AKTU’s Planning Department in Lucknow.

Acknowledgment: The author sincerely thanks the IMPRI team for their valuable support.

Disclaimer: All views expressed in the article belong solely to the author and not nececessarily to the organisation.

Read more at IMPRI:

Buddhism and Cultural Diplomacy: A Bridge in India–Japan Relations

India’s Quiet Digital Revolution: Open Government Data (OGD) 2.0 – 2025