Event Report

Sana Ansari

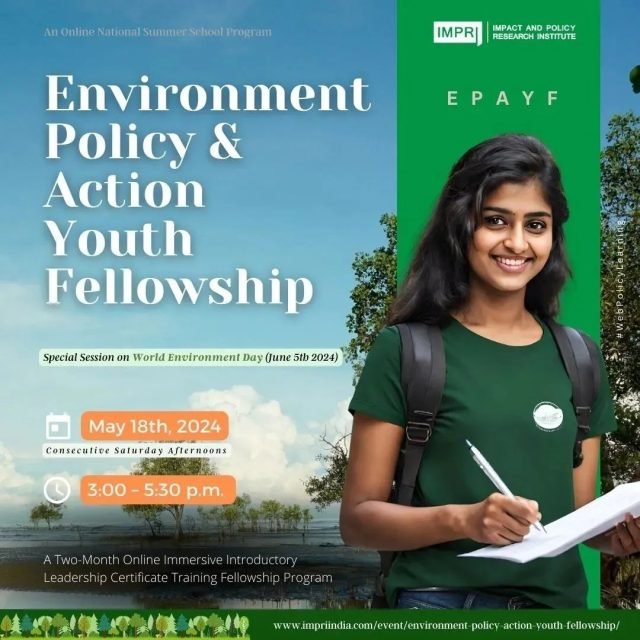

The IMPRI Center for Environment, Climate Change, and Sustainable Development (CECCSD) at the IMPRI Impact and Policy Research Institute, New Delhi, conducted the ‘Environment Policy and Action Youth Fellowship,’ an online international summer school program. This two-month, immersive, introductory leadership certificate training fellowship program ran from May to July 2024. Led by seasoned experts and practitioners in the field, the course offered a unique combination of theoretical insights and real-world case studies. The chair of the course was Ms Bhargavi S. Rao, an independent researcher, educator, environmental activist, and visiting Senior Fellow at IMPRI. The convenors for the program were Dr Arjun Kumar, the Director of IMPRI, and Dr Simi Mehta, the CEO & Editorial Director of IMPRI.

Day 1| Environment Policy and Sustainable Development: Issues and Challenges and Environment Action through Participatory Governance

Diving into the critical issue of environmental policy and sustainability, the session began by Dr Abi Tamim Vanak with an impassioned overview of India’s sustainability objectives, focusing on climate change mitigation and renewable energy utilisation. The interconnectedness of climate change, biodiversity loss, and environmental degradation was highlighted, setting the stage for an in-depth exploration of sustainability challenges. These challenges were categorised into four main areas. Firstly, the “Knowledge Gap” was addressed, emphasising the importance of scientific insight in tackling environmental issues, with the decline of vulture populations due to diclofenac as an example. The discussion then moved to the “Multifaceted Problem” domain, illustrating the interplay between science and politics in environmental debates, exemplified by the cheetah reintroduction project.

Next, the “Hegemonic Alliance” was examined, where policy decisions often overlook scientific evidence. The Green Revolution’s groundwater depletion was highlighted as a risk of sidelining scientific insights in policymaking. Lastly, “Wicked Problems” such as the conservation versus development debate in the Western Ghats were explored, showcasing the complexities policymakers face in pursuing sustainability. Transitioning from theory to practice, insights into ongoing research were shared, particularly India’s dog population issue, highlighting the gap between policy frameworks and scientific evidence.

Existing environmental policies were critiqued, scrutinising the amended Forest Conservation Act and the Green Credits Program for ecological shortcomings, sparking discussions on climate change mitigation versus biodiversity conservation. The session emphasized the ecological importance of semi-arid landscapes like tropical savannas in carbon sequestration, advocating for a shift in policy terminology and better coordination between ministries to address governance challenges effectively.

The second session of Day 1 focused on a crucial step towards environmental action through Participatory Governance, led by Mr. Tikender Singh Panwar. The session addressed the urgency of environmental sustainability and climate change, focusing on historical missteps in the Himalayas where policies in the 60s and 70s led to environmental degradation. Capitalism’s role in exacerbating the crisis was critiqued, highlighting how profit-driven structures have caused rampant carbon emissions and alienated humanity from nature.

The discussion emphasised the need for participatory governance rooted in grassroots engagement and community involvement. Decentralisation was presented as key to fostering resilience and adaptability against climate change. The importance of adaptive solutions, integrating nature-based approaches with people-centric alternatives, was stressed. Examples from urban planning and disaster management showcased the need for a holistic approach that prioritises equity, resilience, and sustainability, aiming to create a more sustainable and equitable future.

Day 2 |Climate Change: Action, Impact and Way Forward and Environmental Clearance and Forest Clearance.

Talking about the biggest crisis the world is facing today—climate change—Mr Soumya Dutta discussed the intricate challenges posed by this issue and the way forward. He emphasised the interconnectedness of South Asia’s ecological systems, which complicates the isolation of environmental impacts within individual countries due to regional factors such as surrounding water bodies, the Himalayas, and monsoon winds. Climate change has intensified two major issues: heatwaves and water crises. The combination of high heat and humidity, known as the heat index, presents severe health risks, especially in urban areas affected by the Urban Heat Island effect.

The discussion highlighted the inadequacy of heatwave data from the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD), which often fails to reflect the real conditions faced by vulnerable urban workers. Additionally, heatwaves have significantly impacted food systems, exemplified by the decline in India’s wheat harvest due to recent extreme temperatures. The broader consequences include increased atmospheric moisture leading to heavier rainfall and flooding. Climate change also disrupts water systems, with intensified cyclones and rising sea levels threatening coastal regions, while the western coast faces a notable increase in cyclone frequency. India’s climate pledges under the Paris Agreement, though ambitious, face challenges in implementation. Addressing these issues requires systemic changes and enhanced community-level resilience to bridge the gap between policy and action.

The second session of the day was led by Dr Debadityo Sinha which focused on the intricate nature of environmental law, which intersects with various sectors and addresses both historical and future impacts. Environmental law not only aims to protect human rights but also emphasises the interconnectedness of ecosystems (ecocentrism). Influenced by local movements such as the Chipko Movement and Narmada Bachao Andolan, environmental legislation in India is guided by several core principles: the mitigation hierarchy, precautionary principle, sustainable development, public trust doctrine, polluter pays principle, and absolute liability. However, adherence to these principles in practice often falls short.

The foundation of environmental legislation in India was laid after the 1972 Stockholm Conference and has evolved with the creation of bodies like the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) and the introduction of laws such as the Wildlife Protection Act, Water Act, Forest Act, Air Act, and Environment Protection Act. The Supreme Court of India has been instrumental in enforcing these laws, establishing doctrines such as absolute liability, and supporting institutions like the National Green Tribunal (NGT). Despite these advancements, challenges persist, including reactive policy-making, weak implementation, legal loopholes, and the influence of political and corporate interests, which collectively undermine the effectiveness of environmental protection efforts.

Day 3| Environmental Governance, Economy and Development, Agrobiodiversity and Nutritional Security and Environment, Social and Governance.

Exploring the intricate relationship between environment, economy, and governance, the session by Prof. Krishna Raj highlighted the interplay between these elements and their impact on the current environmental state. Environmental governance was defined as the regulatory processes and mechanisms through which political actors influence environmental actions, encompassing changes in incentives, knowledge, and decision-making. The discussion emphasised that economic activities are central to environmental issues, underscoring the need to balance environmental, economic, and social goals. Since India’s economic liberalisation in 1991, capitalist policies have led to increased income inequality and environmental degradation, evidenced by rising temperatures in cities like Delhi. The UN IPCC AR-6 report predicts a troubling acceleration in global warming.

Criticism was directed at neoliberal economic policies and neo-classical economics for assuming natural and man-made resources are substitutable, leading to a lack of emphasis on sustainability. Despite advancements in understanding economic growth and sustainability, international organisations often support conflicting approaches. In India, current economic policies, which prioritise growth, have resulted in poor environmental performance and social indicators. Economists have highlighted the shortcomings of existing policies, noting rising inequality and environmental harm. The session concluded by questioning whether current economic development strategies are worth the cost to the environment and society.

Highlighting the interconnectedness of agriculture, biodiversity, and nutritional security, the session by Dr Parashram Patil began by noting that despite India’s economic progress, agriculture remains central to its economy, supporting two-thirds of the population and contributing 19% to GDP. Historically, the Green Revolution transformed India from a food-deficient to a food-surplus nation, yet paradoxically, 40% of the population suffers from malnutrition. The focus on cash crops since the Green Revolution has led to a reduction in crop diversity, affecting nutritional quality.

For example, high water usage in sugarcane and rice cultivation threatens groundwater levels. Additionally, a lack of awareness about the nutritional benefits of locally available foods contributes to malnutrition. To address these issues, a shift towards organic cultivation is recommended to preserve soil quality and sustain agricultural productivity. However, the high cost of organic farming poses a challenge for small-scale farmers. Integrating agroforestry could help overcome this barrier. Emphasizing crop diversification can enhance nutritional security by reconnecting agriculture with biodiversity. The session concluded with an anecdote on how climate change impacts rice cultivation, underscoring the need for holistic approaches to agriculture.

The final session of Day 3, led by Ms Meena Vaidyanathan, explored the concept of Environment, Social & Governance (ESG), which evolved from the Millennium Development Goals. Introduced by the UN in 2004, ESG aimed to position businesses as key drivers of sustainable change. Despite the development of various ESG evaluation tools and frameworks like GRI in the 2010s, actual implementation remains limited.

Unsustainable practices lead to economic challenges such as scarcity of raw materials, increased costs, higher health burdens, reduced productivity, and restricted operational freedom. Conversely, sustainable businesses add value to stakeholders and often achieve long-term success. Effective ESG adoption requires businesses to recognize its benefits, including attracting investors, improving talent retention, reducing risks, and gaining a competitive edge. Common pitfalls include inadequate progress measurement, an overemphasis on environmental aspects, and failure to integrate ESG into business strategies.

Organisations should begin by investing in ESG education, appointing ESG champions, and establishing robust data collection and reporting systems. In India, SEBI mandates ESG reporting for the top 1000 listed companies through the Business Responsibility and Sustainability Report (BRSR), but MSMEs are exempt, revealing a gap in broader adoption. Addressing these issues involves removing barriers for smaller businesses and demonstrating the tangible benefits of sustainability practices, with incremental changes and supportive measures being crucial for a sustainable future.

Day 4| Disaster Resilience and Environment Action Advocacy

Mentioning the critical issue of disaster resilience, Prof. Anil K. Gupta explained that contemporary sustainability dialogues often focus on climate change, overshadowing the complexity of loss and damage, including system vulnerabilities. Since COP 26, the emphasis on disaster resilience and adaptation has grown.

Prof. Gupta of the National Institute of Disaster Management (NIDM) stressed the need for improved financial mechanisms and competency to implement sustainable development goals and the Sendai Framework. Understanding India’s varied vulnerabilities is crucial due to its geographic and cultural diversity, resulting in differing disaster profiles. Despite advancements in early warning systems, cyclonic disasters still cause significant damage, necessitating studies to identify root causes. India’s strategy includes regulatory measures to enhance energy efficiency and mitigate climate change impacts.

Adapting to changes and managing resources effectively, including adopting a circular economy, is essential. Addressing indirect climate change implications, such as health challenges from migration and disease, is also vital. The rise of Eco-DRR and nature-based solutions (NBS) offers significant potential for resilience, though challenges remain. Building resilience involves strengthening systems, empowering agents, and enhancing institutional capacities. Integrating knowledge into action requires understanding vulnerabilities and applying this knowledge practically. As India aims for economic resilience by 2047, aligning efforts across sectors and translating policies into actionable changes are crucial for achieving sustainable development goals.

From the times when climate change was never a front-page issue to now being an important election and socio-economic factor, Mr Himanshu Shekhar conducted a profound session on Environment Action and Advocacy. He highlighted the emergence of climate change as a significant election issue, driven by its tangible impacts like extreme weather, water scarcity, and agricultural distress. His reports from Bundelkhand reveal a worsening water crisis due to abnormal rainfall patterns. In Jalaun District, farmers’ efforts to find water by digging deeper wells failed, illustrating the dire situation. The region’s limited surface water, coupled with rising temperatures, exacerbates the crisis.

Bundelkhand’s water crisis exemplifies broader environmental challenges in India, with erratic rainfall disrupting traditional water management and reducing water availability. This crisis transcends environmental concerns, impacting agriculture, health, and education, and exacerbating social inequalities. Addressing this requires integrated water management, financial support, education, and community participation. Government initiatives and community efforts are crucial, emphasising sustainable practices and water conservation.

Solving the crisis demands a holistic approach, incorporating environmental conservation, social equity, and economic resilience. The growing political focus on climate change reflects its increasing importance, necessitating inclusive policies and investments in infrastructure, technology, and education to build adaptive capacities and ensure water security.

Day 5| Rivers, Communities, Ecology & Environment. Air pollution & Inter-generational Equity & Circular Economy & Waste management.

We have often heard, “Rivers are the arteries of our planet; they nourish the land and sustain life.” To shed more light on this topic, Mr. Ranjan Panda conducted a session on “Rivers, Communities, Ecology, and Environment.” The declining perception of rivers prompted the Youth for Water campaign, based on a study of forest management in tribal areas. Research around 2017-2018 revealed that indigenous communities excel in conservation practices, viewing forests as ancestral entities. Forest conservation has revitalized local water sources, highlighting water security through availability, access, equity, and stability in management. However, waning youth interest in conservation efforts poses a challenge.

Conferences like the Odisha River Conference engaged youth and stakeholders in water issues, revealing a concerning trend: many young people see taps and bottles as water sources, not rivers. Personal connections to rivers, like the speaker’s bond with the River Mahanadi, underscore the cultural and ecological significance of these waterways. Urban development often disregards this, viewing rivers as water bodies or sources of water services. Dams, while beneficial, significantly impact biodiversity.

Rivers support diverse ecosystems, essential for millions relying on them for livelihoods. Addressing river sustainability demands a holistic approach, integrating ecological, social, and economic perspectives.

The second session of the day on another essential issue of air pollution and intergenerational equity was led by Ms Bhavreen Kandhari. The speaker underscored the vital role of citizen movements in driving societal change, emphasising intergenerational equity and the responsibility of today’s youth in environmental stewardship. She recalled a time in Delhi when clean rivers and air were common, contrasting it with today’s severe environmental degradation and unprecedented heatwaves.

Despite individual efforts, the speaker stressed that government action is crucial. The rise of citizen movements, such as “My Right to Breathe,” highlights the shift towards inclusive activism involving diverse communities. Initiatives like Delhi Trees SOS illustrate grassroots efforts to protect urban greenery. The speaker also acknowledged the influence of global youth movements inspired by figures like Greta Thunberg.

The judiciary’s role in environmental justice is significant, with landmark rulings supporting citizen activism. Collaboration across legal, research, and environmental fields is essential for impactful advocacy. Social media and technology amplify these efforts, but physical presence in protests remains crucial. The speaker called for inclusive stakeholder engagement, particularly of indigenous communities, to protect the environment and ensure a sustainable future for all.

In the final session of the day, Prof. Shyamala Mani discussed Circular Economy and Waste Management, contrasting it with the traditional linear model of consumption, where items are used and discarded. The circular economy focuses on reusing, recycling, and repurposing materials to reduce waste. Key aspects include the importance of biodegradable waste, which decomposes easily and can be used for composting, and the challenges with non-biodegradable materials like plastics.

Urban and rural waste management practices vary, with urban areas using controlled composting due to space and odour issues. Effective circular economy practices involve integrating renewable energy, reducing waste through careful planning, and considering the entire lifecycle of products. Waste pickers play a crucial role in recycling, yet economic growth metrics often overshadow traditional repair skills.

Achieving sustainability requires a holistic approach, addressing both environmental and social impacts, including the need for better waste management in rapidly urbanising areas. Collaborative efforts and innovative practices are essential for effective waste management and circular economy integration.

Day 6| Climate Action towards Sustainable development and Forests, soil, biodiversity & Environment.

The session on “Climate Action & Planetary Sustainability” by Dr Ram Boojh, emphasised the interconnectedness of global environmental observances, such as World Environment Day and World Ocean Day, stressing the urgent need to tackle the “triple planetary crisis” of climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution. Climate change disrupts ecosystems, biodiversity loss weakens their resilience, and pollution degrades natural habitats. Addressing these issues requires adhering to planetary boundaries and achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including climate action and life on land.

The discussion highlighted the importance of education, public awareness, and innovations in technology and policy, such as renewable energy and sustainable agriculture. Global cooperation and climate finance are crucial, particularly for developing countries. India’s commitment to achieving net-zero emissions by 2070 and its Panchamrit strategy were noted as significant steps. Despite challenges like political and economic constraints, a complex approach integrating science, policy, and community efforts is essential for ensuring a sustainable and resilient future.

The second session, led by Prof. Sas Biswas, explored forests, soil, biodiversity, and environmental conservation. Drawing insights from ancient texts like the Gita, it highlighted the importance of living harmoniously with nature. Forests, which cover about 24% of India’s land area, are vital for ecological balance and climate change mitigation.

The session addressed challenges such as forest fires, soil erosion, and deforestation, and discussed strategies like reforestation and sustainable practices for improvement. Biodiversity conservation was emphasised, focusing on both in-situ and ex-situ methods to safeguard species and genetic diversity. The impact of climate change on forests, including increased fires and pest outbreaks, was also covered. Special attention was given to the environmental benefits of mangrove ecosystems, bamboo, and urban forestry.

The session reviewed legal frameworks like the National Forest Policy and international agreements such as the Paris Agreement, stressing the need for effective implementation and global cooperation. Community engagement, education, and technological advancements in monitoring and conservation were highlighted. The session concluded with a call for integrated approaches to address environmental challenges and promote sustainability.

Day 7| Environment Action for the Future, Environment, Social Inclusion, Communities and Natural Resources & Women and Environment Action.

Day 7 of the Environmental Policy and Action Youth Fellowship focused on “Environment Action for the Future,” by Mr Nityanand Jayaraman, covering social inclusion, communities, natural resources, and women’s roles in environmental action. Mr. Nityanand Jayaraman, an environmental activist, presented a keynote on “false solutions,” critiquing superficial fixes that often worsen underlying issues. He identified four characteristics of false solutions: discriminatory impacts, crisis management without addressing root causes, oversimplification of complex problems, and reliance on techno-fixes without considering structural inequalities. He used Chennai’s Elcot SEZ as an example, showing how it disrupted ecosystems and increased flooding.

The case study emphasised the drawbacks of prioritizing economic development over natural infrastructure, such as intensified flooding and heat islands. It challenged the notions of “development,” highlighted false solutions, and criticized the unequal benefits and inadequacies of techno-fixes. Panellists stressed the importance of gender-sensitive policies and grassroots involvement, as well as the pivotal role of youth in driving environmental change. The session concluded with a call for actionable policies and collaborative efforts towards a more equitable and sustainable future.

The second session led by Prof. Vibhuti Patel focused on the intersection of women and environmental action, highlighting the historical and contemporary significance of ecofeminism. It began with a reflection on the Chipko Movement of the 1970s, where women in India protested deforestation by embracing trees, becoming a symbol of grassroots resistance and ecofeminism. Ecofeminism, which emerged in the 1970s, connects the oppression of women with the exploitation of nature, arguing that both are affected by patriarchal and capitalist systems. It advocates for dismantling these hierarchies to address ecological and social injustices.

The session highlighted global ecofeminist figures such as Vandana Shiva and Wangari Maathai, who address issues like industrial agriculture, biodiversity loss, and desertification, demonstrating the impact of women-led environmental movements. Challenges such as climate change and resource depletion were discussed, particularly their disproportionate effects on marginalised communities. An intersectional approach to ecofeminism, which includes the experiences of indigenous women and women of colour, was emphasized. The session concluded with recommendations for policy advocacy, community engagement, and education, urging participants to integrate ecofeminist principles into their work for a more equitable and sustainable future.

On the third day, the final session was on Environment, Social Inclusion, communities and Natural Resources by Ms Bhargavi S Rao which reflected on Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring,” emphasising the need to move away from unsustainable industrialization and focus on environmental protection. Key issues discussed included land grabs for development that displace small farmers and disrupt wildlife habitats, often without adequate compensation, leading to socio-economic and environmental problems.

The session highlighted the impact on local communities, including the displacement of farmers and youth migration. Gender dynamics were also addressed, with a focus on how women in marginalised communities face disproportionate burdens. Criticisms were made of current environmental laws for often prioritising industrial interests over ecological health.

A shift towards sustainable development was advocated, balancing environmental protection with social justice. Recommendations included strengthening environmental regulations, empowering communities through decentralised decision-making, and integrating sustainable practices into education. The session concluded with a call for active participation in policy-making and collaboration to address environmental challenges, emphasising a commitment to a more sustainable and equitable future.

Day 8| Environment, climate change discourse: Business as Usual & Environment and Future.

On the final day of the course, the session was titled “Environment and Climate Change Discourse – Business as Usual” by Mr TK Arun. He addressed the climate crisis driven by fossil fuels and the slow transition to renewable energy due to economic, political, and infrastructural challenges. He emphasised the need for a complex approach to reduce fossil fuel use, promote renewable energy, and implement sustainable practices. As India’s energy consumption rises with economic growth, it will likely rely on conventional sources like coal and natural gas. However, balancing developmental needs with environmental responsibilities is essential. Solar power, despite its benefits, faces integration challenges due to grid stability issues and hidden costs.

Innovative storage solutions such as thermal energy storage, pumped hydro, and green hydrogen were discussed as alternatives to traditional battery storage. The importance of addressing environmental impacts and ensuring equity in climate action was highlighted, with an emphasis on holding wealthier nations accountable for their historical contributions to climate change. The session concluded with a call for stronger environmental regulations, community empowerment, and integrating sustainable practices into education. The urgency of reducing fossil fuels and transitioning to renewable energy was underscored, aligning with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) goals to limit global warming.

The valedictory session on “Environment and Future” by Dr Jyoti Parikh began with an overview of how atmospheric changes impact the climate, emphasising the critical role of energy. It was noted that both renewable and non-renewable energy use affects the environment and contributes to climate change. Global energy consumption trends underscored the urgent need for decarbonization. Comparisons of efforts to reduce poverty and energy consumption highlighted significant progress in China and Brazil.

The correlation between GDP growth and energy use was explored, noting that increased energy consumption often indicates economic growth but can also lead to environmental degradation. The relationship between population growth and energy demand was discussed, particularly how agricultural and domestic activities drive energy needs. Both China and India are stabilising their populations, with India surpassing China. The session covered aspects of the atmospheric environment, including air pollution, global warming, and ozone depletion, and noted a significant decrease in per capita CO2 emissions, reflecting increased awareness of sustainable development goals.

The evolution of energy consumption was traced from biomass to modern renewable sources. The pros and cons of renewable energy were discussed, emphasising the need for storage solutions and addressing challenges like unpredictability and high initial costs. The potential of hydrogen as a clean energy carrier was highlighted, along with its applications and challenges. The shift towards renewable energy was emphasised, noting the importance of energy storage and the role of digital technologies in energy transition. Societal changes driven by the internet were also discussed, particularly in community building and eco-conscious choices. The session concluded by stressing the importance of a diverse mix of renewable energy sources, significant investment, financial restructuring, and global cooperation for a sustainable energy transition.

Acknowledgement: This article is written by Sana Ansari, a research intern at IMPRI, pursuing Master’s in Public Policy at St. Xaviers College Mumbai.

Read more at IMPRI:

Urban Policy and City Planning- Cohort 2.0

Healthcare Sector Management and Governance: An Indian Perspective