Tanuj Samaddar

Sampurna Biswas

Abstract

This article examines the ever-existent problem of water scarcity in Rajasthan with a special focus on the district of Barmer, and its direly grave socio-economic implications on agriculture, health, and education. In their periods of water shortages, the systems and policy frameworks in place fail to uphold themselves perpetuating the unending cycle of poverty. Micro-irrigation, solar irrigation, and polyhouse production techniques have emerged as viable and sustainable solutions in addressing these problems. Similarly, these new technological advances and inlet-water management help agricultural production, income generation, as well as off-farm job creation in their own right. This study underscores the transformative potential of technology in mitigating Barmer’s water crisis and fostering socio-economic resilience.

1. Introduction

Scarcity of water has been a chronic problem in the district of Barmer along the Indo-Pak border. Barmer is Rajasthan’s second largest district and is important as a resource pool for metallurgical industries. Several immediate socio-demographic and economic repercussions of this glaring problem have been observed, such as but not limited to the rise in dropout rates, death caused by contamination among others. This constituency has long been beset by a number of environmental challenges, with water shortages being perhaps the most urgent among them.

2. On Ground Reality – The Case of Barmer

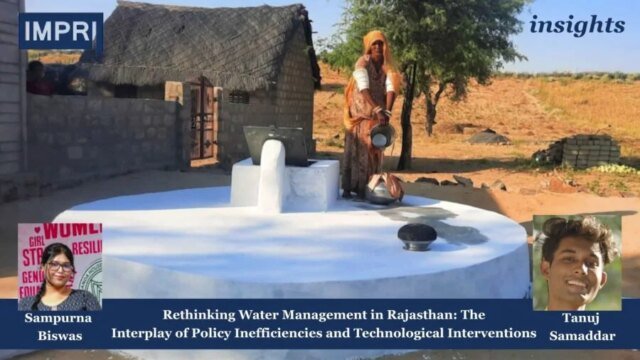

Barmer is among the most arid districts of Rajasthan that is experiencing perennial temperature and weather extremities. All such extreme conditions have profoundly affected the lifestyle of the inhabitants, from the formation of their habitations to their traditional costumes and cuisines. But in the district of Barmer these realities are stark as the local inhabitants, especially the womenfolk, take the harshest toll of the situation.

As per a survey conducted by the Human Welfare Foundation young girls of the family are forced to walk 2 km one way from their hutments (dhani) to bring merely a pot of water, a task which they had to perform nearly thrice a day, taking up more than 4-6 hours of their time daily.

The absence of consistent water supplies also takes a heavy toll on agriculture in the area. What further aggravates the situation is frequent crop failures plaguing the region. Most of the inhabitants depend on the scanty rainwater that infiltrates deep below the soil out of the reach of evaporation.

2.1 Financial Constraints

In such a situation, the residents are significantly reliant on deep wells which constitute the primary source of their drinking water. Each of these wells cost an estimated 1,25,000 rupees to be constructed, something which the local inhabitants could hardly afford to pay.

2.2 High Dropout Rates

The schooling of the youths also bears the brunt of the crisis as the rate of school dropout after primary schooling remains a staggering 98 percent .

3. State Level Implementational Failures and Delays

Though local effects of water scarcity are grim, systemic shortcomings like policy inefficiencies and political delays have also contributed to exacerbating the issue. ERCP (Eastern Rajasthan Canal Project), which has been planned to cater to the drinking and irrigation water requirement of vast tracts like Barmer, has suffered repeated postponements until in 2023 it was finally granted the status of a national project by the central government. However, even after tripartite

MoUs, central funds and support have been tardy, and local interest has been routinely sacrificed to cater to the demands of the neighbouring states.

Similarly, the Barmer Water Lift Canal Project, for example, was opened by the Congress regime in the state in 2003 and was scheduled to be completed within 2007. In 2003, however, the Bharatiya Janata Party regime in its first stint of power put the project on hold for nearly four years, only to restart work on it once again in 2007.

In addition to state-level infrastructure failures such as the ERCP and Barmer Water Lift Canal Project, another relevant example of political ineptitude can be found in the farmer loan waiver issue which demonstrated how political interests have also influenced financial policies. Rajasthan saw massive farmer protests ahead of the state assembly elections in 2018, the then BJP led government announced a loan waiver of upto Rs 50,000 to farmers holding up to two hectares of land.

Since a majority of farmers in the region hold five to 10 hectares of land, they did not receive waivers. Such a political interest driven approach towards policy formulation gives birth to naive policies which Dr. Noam Angrist, a governance expert from the Blavatnik School of Government (University of Oxford) highlights it as ‘unrealistic’ and implemented without considering the actual condition of the target demographic.

4. How tech is driving change in Rajasthan

Novel technological innovations in irrigation and water conservation, ranging from micro-irrigation systems to polyhouse cultivation, have profoundly changed the face of farming in Rajasthan, offering a glimmer of hope despite the delays and inefficacies in policy implementation.

4.1. Micro-Irrigation

Rajasthan, has primarily adopted the methods of sprinkler irrigation and drip irrigation on a large scale to offset water shortage and enhance agricultural yields, mainly in its water-deficient districts including Barmer. Government evaluations and sector studies find large yield gains in horticulture and vegetable crops under micro-irrigation.

Consistent watering allows farmers to switch from low-value grains to more valuable vegetables and fruit trees, which boosts household cash income and also lessens seasonal hardship. As irrigation becomes less laborious and more reliable, women’s daily patterns of labour alter, some time is freed for other income or household chores, though the net effect varies by village. The resultant higher per-acre output encourages local aggregation, small traders, and sometimes cold-storage investments creating non-farm jobs.

4.2. Solarised Irrigation

Solarised irrigation and renewable energy in pumps implies substituting diesel or subsidised grid power for irrigation with sun through off-grid solar pumps, farmer-level pump or grid connected land-based solar plants. Policies such as PM-KUSUM in India encourage this with the help of subsidies and new business models.

Rajasthan has taken a lead in this regard with the state commissioning both stand alone pumps as well as grid connected decentralised solar plants. More than 1,000 MW of projects under PM-KUSUM and state programmes have been set up enabling around 100,000–170,000 farmers to access daytime solar power for irrigation without relying on diesel or costly grid supply at night.

The social effects are also notable. Daytime irrigation now aligns with crop watering needs, raises efficiency, and supports higher yields, which increase farm incomes and give farmers more time for family activities or small enterprises.

4.3. Polyhouse Technique

Large scale implementation of Polyhouse techniques across the state has been adopted in Gurha Kumawatan. This technique has alleviated farmers in the region out of acute poverty and ensured sustained income perennially. The same technique is practised in Israel with an annual rainfall of around 508 mm and can be scaled up in Rajasthan as well.6 The example of Gurha Kumawatan is a reminder that the state has the potential to sustain polyhouse agriculture and hydroponics.

5. Conclusion

The chronic shortage of water in Barmer has resulted in catastrophic socio-economic consequences, especially in relation to education and livelihood, affecting mostly women and children. Systemic issues with delayed policy action have further deepened poverty while constraining developmental prospects. Emerging forces driving agri-dynamics of the region now put innovation in technology, such as micro-irrigation, solar pumping, and polyhouse technology. Along with providing sustainable water management solutions, these technologies establish economic resilience through enhanced agricultural productivity, income opportunities, hence off-farm employment.

References

About the contributor: Tanuj Samaddar is a final-year undergraduate at Kirori Mal College, University of Delhi. He is a presidentially recognised artist, researcher, and public policy enthusiast. He is a fellow of DFPGYF Diplomacy, Foreign Policy & Geopolitics Youth Fellowship- Cohort 2.0.

Sampurna Biswas is a sophomore at Miranda House College, University of Delhi. She takes great interest in teaching, child psychology and geography. She is a fellow of DFPGYF Diplomacy, Foreign Policy & Geopolitics Youth Fellowship- Cohort 2.0.

Disclaimer: All views expressed in the article belong solely to the author and not necessarily to the organisation.

Read more at IMPRI:

India IPO Surge, US Political Headlines & Bihar Polls

Acknowledgement: This article was posted by Shivashish Narayan, a visiting researcher at IMPRI.