Policy Update

Jayasree

Background

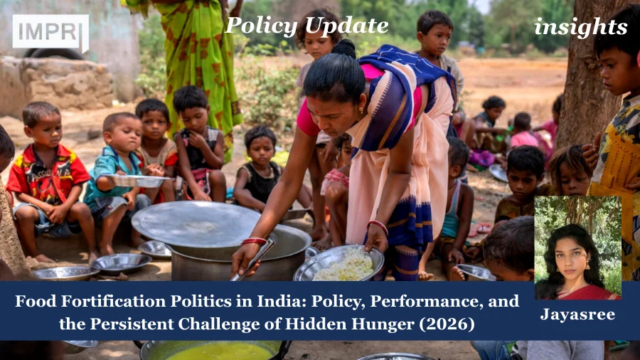

Food fortification is scientifically defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as the practice of deliberately increasing the content of one or more essential micronutrients (i.e. minerals and vitamins, including trace elements) in a food so as to improve the nutritional quality of the food supply and provide a public health benefit with minimal risk to health. From the purview of public policy in the Indian context, it deals with the state intervention or government efforts to combat malnutrition and other deficiencies via structured public policy schemes in the food sector.

(Source: IntechOpen)

These schemes lay down the frameworks for the mandatory addition of vitamins and minerals to staples like rice, wheat flour, oil, salt, and milk. Some of these public schemes include the Public Distribution System (PDS), Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), and midday meals. The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) sets the standards for these policies that are later approved by the cabinet.

Functioning

The necessity for food fortification in India:

India ranks 102nd out of 123 countries with a “serious” score of 25.8 in the Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2025. GHI is inclusive of indicators such as undernourishment, child stunting, child wasting, and child mortality. The data shows that in India around 15% of the population faces insufficient calorie intake, 35% of children are stunted, and 18% of children under five are wasted, i.e., have dangerously low weight-for-height, but have faced a decline in child mortality due to improved healthcare access.

(Source: Vision IAS)

This slow progress in its path towards zero hunger makes India gravely vulnerable given its position in the hidden hunger. India is a land of gastronomic diversity, yet the majority of its population follows a monotonous diet of staples. The poor dietary choices, food insecurity, and lack of awareness contribute to the deterioration of the health of the population. For decades, the Indian government has worked to enhance the nutritional quality and access to food via wide-ranging socio-economic schemes, community health policies, and welfare measures.

Performance

Timeline of food fortifications in India:

(Source: Tata Trusts)

The first food to be fortified was vegetable oil, followed by Vanaspati (hydrogenated oil) with vitamins A and D to combat deficiencies in rural and urban diets in 1953. The next food fortification in 1962 was an idea borrowed from the French, where salt iodization was started to protect the health of the public from goiter. This revolutionary idea was further actualized in the 1990s to cover a larger public by the National Iodine Deficiency Disorders Control Program. The legislation was repealed in 2000 and then reinstated in 2005. Further, mandatory salt iodization was enforced in 1998. These constitute the early initiatives undertaken by the government of India.

The decades of the 2000s and 2010s witnessed policy standardization that fortified staples such as wheat flour, rice, milk, and edible oil. These include the FSSAI operationalization of standards via the National Summit for the mentioned staples as well as double-fortified salt in 2016. A public-private partnership across the country was formalized for the fortification of milk in 2017. The Milk Fortification Project was led by the National Dairy Development Board (NDDB), involving the World Bank (SAFANSI), Tata Trusts, and FSSAI. In 2018, the Anemia Mukt Bharat strategy was implemented to fortify rice with iron, folic acid, and vitamin B12.

Rice and wheat are ideal edible missionaries for micronutrient delivery through fortification in India due to their widespread consumption. However, the delay in its fortification policy formulation and implementation has greatly impacted the pace of fighting nutritional deficiencies.

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The recent years have witnessed wide-ranging schemes and policies by the central government focusing on food fortification in India.

- POSHAN Abhiyaan was launched in 2018 with the main objective of improving the nutritional status of children, adolescent girls, and pregnant and lactating mothers.

- Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana was launched during COVID-19 to provide free food grains (5 kg/person/month) to the poor, in addition to subsidized rations.

- PM POSHAN is a mandatory but free school meal program in India designed to enhance the nutritional status of school-age children nationwide.

- Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) was revamped as Mission Saksham Anganwadi and POSHAN 2.0, focusing on early childcare and vulnerable women’s healthcare.

The rise in centrally sponsored schemes shows the government’s commitment to eliminating a malnourished, hunger-stricken, and nutritionally impaired India. The phased roll-out and pilot-based implementation seek to establish a sustainable food fortification model. There has been an increase in the budget for a high-return health investment by the union government, especially the nationwide distribution of fortified rice. The Union Cabinet approved ₹17,082 crore (approx. $2.1 billion) for its continuation under government schemes until December 2028, covering 100% of costs, while annual costs for rice fortification are estimated around ₹2,500-₹2,700 crore, considered instrumental in fighting malnutrition and anemia.

(Source: forumias.com)

However, an assessment of the structural frameworks and policy instruments reveals a lot of discrepancies in ascertaining the impact of food fortifications.

Issues in food fortification in India:

(Source: Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition)

- There is an inconsistency in the implementation of policies and schemes across the states due to weak coordination, enforcement, and monitoring mechanisms. While the budget allocations increase annually, there has been inadequate investment in infrastructure, food research and development, culinary development, and science.

- The PDS, a crucial socio-economic tool in rural nutritional accessibility, is burdened and fragmented by issues of corrupt management, poor infrastructure, regulatory oversight, and unfair distribution of fortified food to non-targeted privileged groups.

- The safety net and fortification levels in the food produced in India fall way below the WHO’s recommended levels. For instance, the 2018 regulations by the FSSAI permit adding only 75-125 micrograms (mcg) of folic acid and 0.75-1.25 mcg of vitamin B12 per kilogram of wheat flour or rice, which is 90% less than the stipulated level prescribed by the WHO.

- The unregulated fortification centers across the country cause overdosing of nutrients, risking medically weaker populations, such as cases of iron overload in those with thalassemia or infections.

- There has been a surge in sidelining of traditional dietary diversity and cerealization of foods, leading to increasing lifestyle diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.

Way Forward

- FSSAI, with the help of private organizations, international actors, and state-level coordination, should establish federal monitoring and compliance to ensure fortification of staples to meet WHO standards.

- States should prioritize dietary diversity and risk-based non-fortified alternatives to medically vulnerable populations, mitigating the risk of nutrition overload.

- Integration of dietary awareness amongst the population in government schemes is essential to combat cerealization. Promotion of nutritional food groups such as pulses and millets, along with the consumption of fortified foods, would hasten the process of elimination of hidden hunger.

- Sustained innovation and investment are essential in developing cost-effective food fortification mechanisms.

The trajectory of food fortification politics would be effective, inclusive, and high-yielding if these ideas were materialised by the government bodies of India.

References

de Benoist, B. (2005). Food fortification: good to have or need to have? Maternal and Child Nutrition, 1(3), 136–138. Retrieved from https://www.gainhealth.org/resources/reports-and-publications/food-fortification-good-have-or-need-have

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2001). Food fortification technology. In Food, Nutrition and Agriculture No. 27/28. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/4/w2840e/w2840e0d.htm

Food Fortification Initiative. (2025, August 4). The new publication raises concerns that India’s food fortification standards are insufficient. Retrieved from https://ffinetwork.org/concerns-that-indian-food-fortification-standards-are-insufficient/

Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN). (n.d.). Staple food fortification – crucial fight against malnutrition in India. Retrieved from http://www.gainhealth.org/events/staple-food-fortification-crucial-fight-against-malnutrition-India

Gordon, C. M., DePeter, K. C., Feldman, H. A., LeBoff, M. S., & Friedman, A. J. (2008). Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among healthy infants and toddlers. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 162(6), 505–512. doi:10.1001/archpedi.162.6.505

NITI Aayog. (2023, March). Large-scale staple food fortification as a complementary strategy to address vitamin and mineral vulnerabilities in India: A critical review. Retrieved from https://www.niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2023-03/Large-scale-staple-food-fortification-as-a-complementary-strategy-to-address-vitamin-and-mineral-vulnerabilities-in-India-A-critical-review.pdf

NSS Research Journal. (n.d.). [Untitled PDF document]. Retrieved from https://www.nssresearchjournal.com/CertEdiDoc/CurrentEdition2f6d9c07-83be-4239-bdab-6a3d0b6a70b7.pdf

World Health Organization, & Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2006). Guidelines on food fortification with micronutrients. Geneva, Switzerland: Authors. Zimmermann, M. B., Jooste, P. L., & Pandav, C. (2008). Iodine-deficiency disorders. The Lancet, 372(9645), 1251–1262. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61005-3

About the Contributor

Jayasree is a research intern at IMPRI (Impact and Policy Research Institute), and is currently pursuing her bachelors in political science from Madras Christian College, Chennai.

Acknowledgement

The author sincerely thanks Aasthaba Jadeja and IMPRI fellows for their valuable contribution.

Disclaimer

All views expressed in the article belong solely to the author and not necessarily to the organisation.

Read more at IMPRI

Trump’s Nobel Peace Prize Case Explained: Military Spending, Gaza Ceasefire and U.S. Dominance Shift