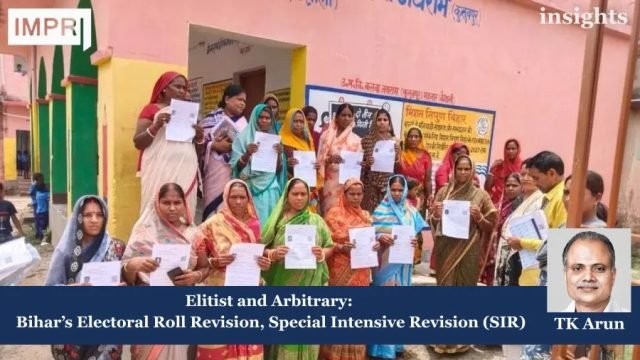

TK Arun

Supreme Court should dismiss EC’s contentions on Special Intensive Revision of Bihar’s electoral rolls as elitist, contradictory and subversive of democracy.

The defining character of the Election Commission (EC)’s ongoing drive for Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of Bihar’s electoral rolls is its elitism, and its operating mechanism violates the basic principle of natural justice—that an accused person is innocent until his or her guilt is established.

The EC’s assertions, granting it exclusive authority to decide who is an eligible voter, are little more than overweening conceit. Its assumptions are riddled with contradictions.

The Supreme Court should dismiss the EC’s contentions and separate a thorough revision of the Bihar electoral rolls from the forthcoming assembly elections. This would ensure that the November elections are held on the basis of the existing rolls, modified as usual by exclusions and additions as per the EC’s own regular practice. The apex court should also mandate the EC to honour the commission’s own voter ID cards, Aadhaar, and ration cards as valid documents that establish the holders’ eligibility to vote, whenever a thorough revision of the rolls is undertaken.

Rejections Must Be Backed by Proof

Should dead persons, fake voters, people whose names appear on electoral rolls in multiple states, and illegal immigrants be allowed to vote? asks the commission, in rhetorical rebuttal of the opposition to SIR. By deeming such a response adequate to refute criticism, Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) Gyanesh Kumar shows contempt for the intelligence of critics.

If a booth-level officer finds that someone listed on the electoral rolls has died, he can strike that name off—and no one would object. If a name on the list does not correspond to any real person, that name too can be struck off. If the same person has registered to vote in multiple states, that can be remedied without protest. But if someone is deemed ineligible to vote on account of not being a citizen, such alienness must first be proven before his or her name is struck off. Whoever objects to that person being given the right to vote should be required to prove that the person is a non-citizen.

Why Are 2003 Rolls Sacrosanct?

The EC is willing to accept the authenticity of the 2003 electoral rolls. Proof that a voter or his or her parents figured in the 2003 electoral roll is considered sufficient proof of eligibility for inclusion in the 2025 rolls. But why should the 2003 electoral roll—prepared on the basis of identity documents such as voter ID cards issued by previous ECs and ration cards—be considered any more authentic than subsequent ones?

On what logical basis, given the presumed fallibility of ration cards and Elector’s Photo Identity Cards, does the commission rule out the possibility that foreign nationals and fake voters might also have wormed their way into the 2003 rolls?

Illogical Demands

How is a poor, semi-literate person, whose home and meagre belongings may have been washed away by floods multiple times, supposed to establish his or her citizenship? The EC has provided a list of 11 documents it believes will suffice. Pension orders or ID cards from the government or a public sector undertaking is one. But what proportion of Indians have worked for the government? While the world average for public sector employment is about 7 per cent, in India the figure is closer to 2 per cent.

A passport is another document. Yet less than 10 per cent of Indians hold one. According to the Ministry of External Affairs (2022), a quarter of all passports have been issued to people in Kerala or Maharashtra.

Another eligible document is a matriculation or degree certificate issued by a state board or university. This defies logic. If a family of illegal migrants settles in India and enrols a child in school, and that child later completes matriculation, the EC, in its magical thinking, considers that sufficient to prove citizenship.

Queer Case of Birth Certificates

Birth certificates issued by a competent authority bestow entitlement. For those born after 1989, registration of births was made mandatory. But is anyone certain that all births and deaths are meticulously registered?

Institutional childbirth is still being promoted by offering incentives to mothers to deliver their babies at hospitals or clinics. Such births are generally registered. But what about births that still take place at home, presided over by a midwife—how many of those are registered?

And what of those whose bodies floated in the Ganga during the worst phase of the Covid pandemic? Did they conscientiously register their virus-stricken end at the village office before launching themselves into their watery grave?

The EC acknowledges that not everyone may be able to produce a birth certificate. In such cases, it suggests parents’ birth certificates as proof. But what proportion of India’s landed gentry would be able to furnish their parents’ birth certificates? Very few. And what proportion of India’s landless labourers could do so? Even fewer. Given the quality of land records in India, even the landed elite would struggle to establish their title to the land they occupy.

Unrealistic Expectations

Residency certificates, caste certificates, house or land allotment certificates, and family register certificates will also suffice, says the EC. Yet residency certificates today are issued on the basis of Aadhaar, effectively making them proxies for Aadhaar. Caste certificates are obtained only by a small percentage who seek higher education or government jobs. And can the EC be certain that all house allotments under government schemes were made after verifying the citizenship of the beneficiaries?

In a land as vast and as poorly governed as India, at least in large parts and for long periods, expecting everyone to possess authentic documentary proof of citizenship is unrealistic. Only the elite would have such documents. The rest would come up with ration cards and, these days, Aadhaar—documents that are the closest thing available to proof of belonging to this land.

Onus on EC

If, in spite of being able to produce these ubiquitous documents, a person is still suspected of not being a citizen, the onus should be on the EC and its officers to prove that person’s ineligibility to remain on the voters’ list.

By its arbitrary use of power in conducting SIR, the EC is subverting democracy rather than serving it. Dear EC, you are employed in the service of the people, not to lord over them. We, the people of India, are sovereign in our own right, and do not need you as our lord or overlord.

TK Arun is a senior journalist based in Delhi.

The article was first published in The Federal as Bihar electoral roll revision: Elitist and arbitrary, SIR! on 26 July 2025.

Disclaimer: All views expressed in the article belong solely to the author and not necessarily to the organisation.

Read more at IMPRI:

e-ShodhSindhu (eSS) Scheme, 2015: Democratizing Knowledge Access in Indian Higher Education

Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchayee Yojana (PMKSY), 2015: Har Khet Ko Paani & Per Drop More Crop

Acknowledgment: This article was posted by Riya Rawat, visiting researcher at IMPRI.